Documentation online

Art Viewer

Contemporary Art Library

Les Bains-Douches

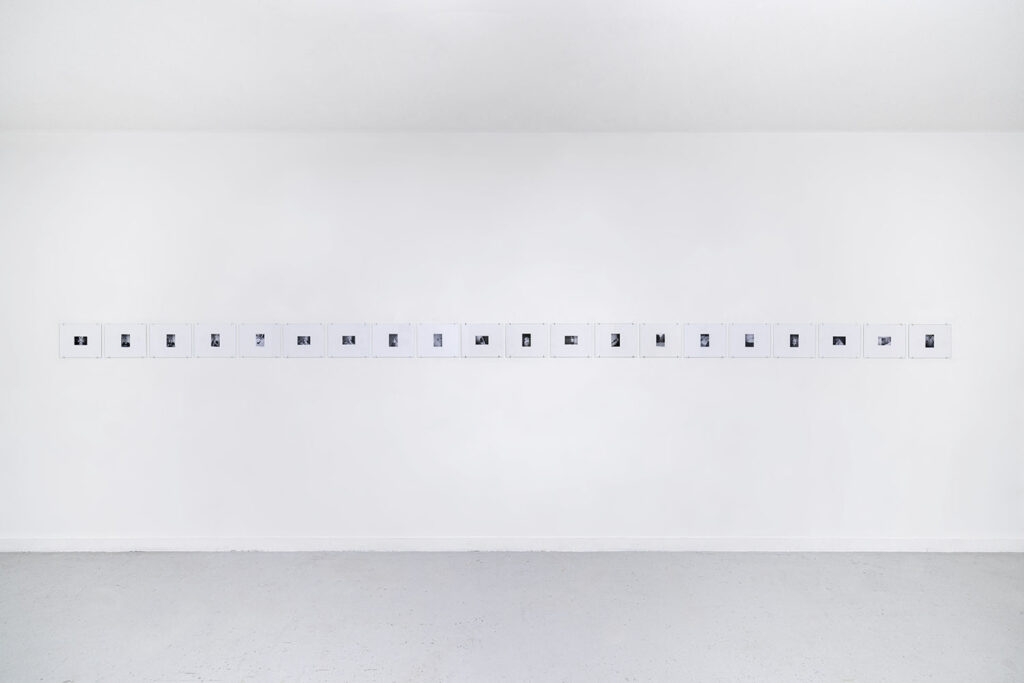

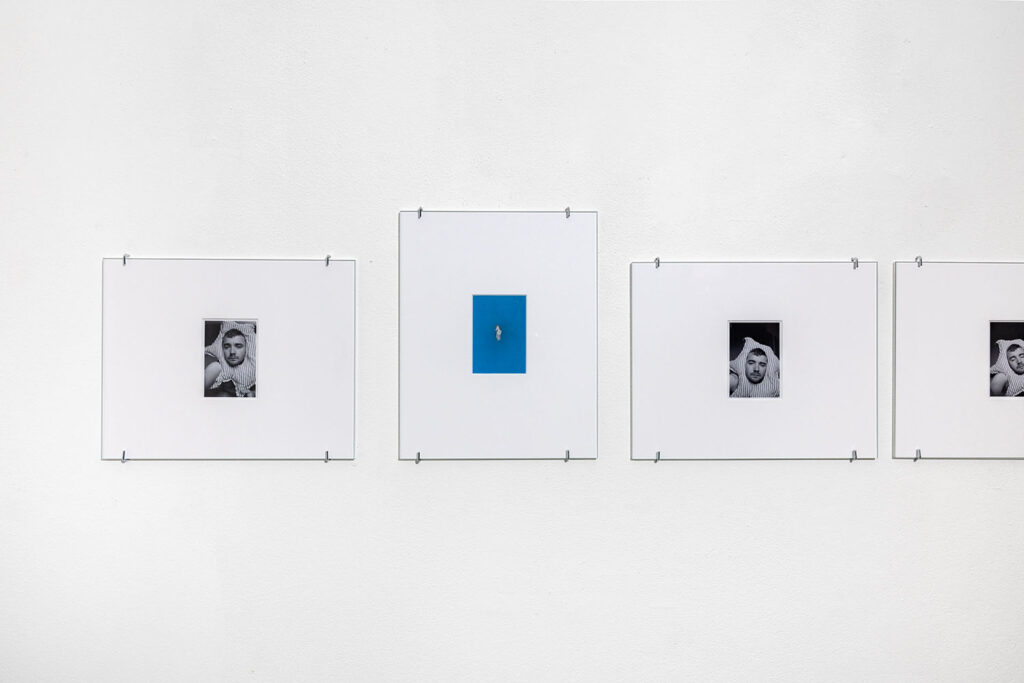

Not so blue

solo show, Les Bains-Douches, Alençon

24 novembre – 23 décembre 2023

Texte de Pierre Ruault

The Skogyrkogarden Cruise: Rambling in the Lands of Sexual Dissidence

« Be proud and happy of what your body exults. Sex is no less noble than sentiment… To make love in the bathrooms and lavatories isn’t about hiding, isn’t about being ashamed. It’s about giving yourself the chance to experience an adventure just around the corner, a moment you know nothing about before going in and thanks to which you feel much more alive coming out.». (1)

At a time when my sexuality remained hidden in the shadows of a burdensome denial, leaving me isolated, a stranger to my own body, cruising was my sole breath of fresh air, the only free space available to me for becoming who I am.

We could define cruising as a drifting on the margins of urban spaces. The wandering of an anonymous individual in search of another, driven by a precise intention, to satisfy that dual pleasure – libidinal and interpersonal at one and the same time – that would be otherwise unthinkable within the conventional social sphere. Stimulated by the fluctuations of carnal appetite, this journey of the mind also resonates in the extensive “personal-ads literature” generated by dating apps. Here I am going to dare something, I am going to draw a parallel with the position of the flâneur as it has been developed by a number of writers, including Walter Benjamin. (2) In the freedom of his wanderings and the developments of his sensibility as a form of knowledge, Benjamin expresses a reaction to the grip of time and the constraints imposed by the contemporary world. By shifting our gaze from the arcades of Paris to the territories of homosexual pick-ups, flânerie enables us to explore the ways individuals take over these public spaces and the social dynamics that follow from that.

Addressing a topic within the framework of an essay on Paul Lepetit’s artistic approach is both imposing and empowering, grounding the writing in personal experience. I opt to wholeheartedly embrace the inherent erratic nature of thought, which is deeply rooted in my autobiographical journey as the exclusive critical and affective standpoint for this text.

A few weeks ago, when I was in Stockholm for a research residency, I was aimlessly walking in the wooded paths of Skogyrkogarden, looking for Greta Garbo’s burial site without really thinking about where I was headed. My reverie was suddenly interrupted when I noticed an unusual scene at the entrance to the public restrooms, which irresistibly caught my eye. Two cars were parked in front of the small building topped by a sign with the same men’s symbol that you find everywhere else. The repeated blinking of the hazard lights announced the presence of individuals while at the same time suggesting the fleetingness of the time they would spend there. It was the same standardized restroom architecture we see in the photographs of Paul Lepetit. The artist recreates here the practice of reappropriation that is peculiar to places where people meet briefly, consisting in projecting on public furnishings a strong element of fantasy. (3)

Unable to repress a slight voyeuristic urge, I stopped to observe them. Two middle-aged men were focused on a strange dance in front of the restroom, entering and exiting by the same doors, with the pace of their passing each other describing perfectly symmetric timing. Their eyes furtively meeting, a mutual recognition whose secret is held by the initiated alone, namely “We recognize each other.” After several long drawn-out minutes that seemed to go on forever, the two men finally decided to withdraw to the inside of the building in absolute silence, shielded from prying eyes, including my own. No need to follow them to grasp what was about to play out in this public urinal. They had come in search of the same thing, the fleeting privilege of belonging to the clandestine “erotic minority.” From that moment on, the question of sexual orientation has no real importance. Homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, there is little chance probably that those two men identify as such. Public urinal pick-ups transcend traditional labels and categories.

Wasn’t it in Sodom and Gomorrah that Marcel Proust brought up the “laws of a secret art” during Baron de Charlus’s encounter with the waistcoat-maker Jupien? (4) The reference, moreover, reminds me that well before I, too, took the plunge, it was through literature that I first confronted the pick-up experience. We could locate this iconography of homosexual seduction within a specific historical core of cultural output going back to the late nineteenth century.

Nevertheless, it is just as captivating to notice certain analogies between the practice of cruising and certain motifs from contemporary art, beyond all queer issues, in particular the performative character strictly speaking. I’ll venture here to place it in an affiliation with the excessive urban spinoffs devised by the Situationists, or Vito Acconci’s performance called Following Piece, (1969), which involved randomly following passers-by the artist crossed paths with in the street. (5) Through an arrangement of actions and gestures that are particularly ritualized, the actors involved in cruising carry out a similar random form of performance. Walk in the woods, wait, show oneself, hide. The question of bodies likewise crops up in observing the choreography of bodies, notably through nonverbal language and the play of bodily poses and eye contact, as well as the question of revealing oneself. We find the same exploration of wandering and reappropriation of public space, making it possible to evaluate daily routines and embody other ways of being in the world.

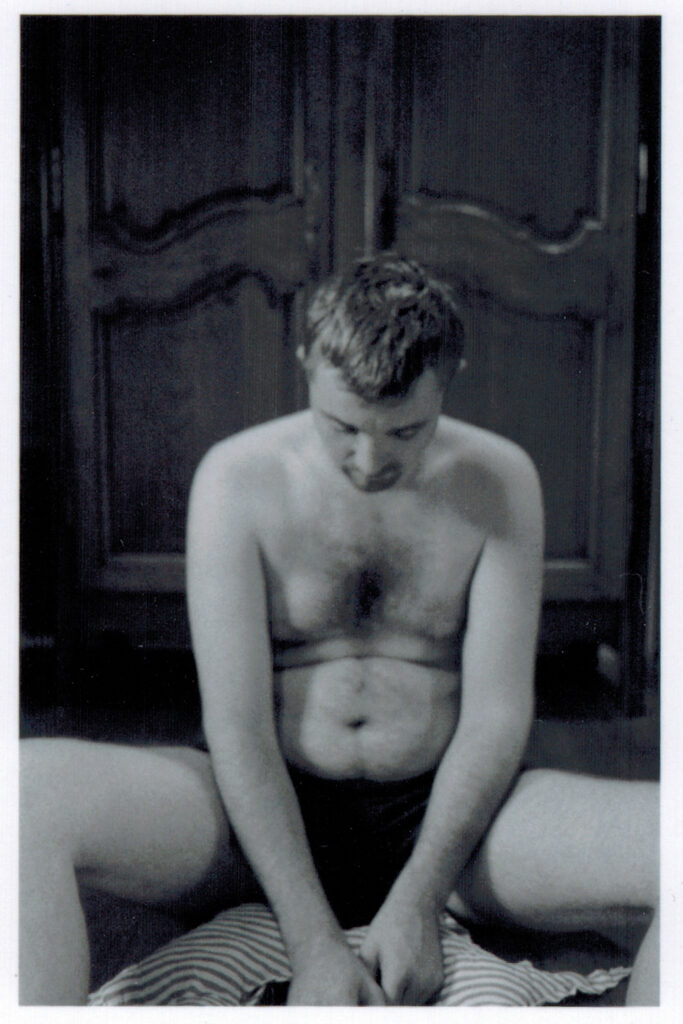

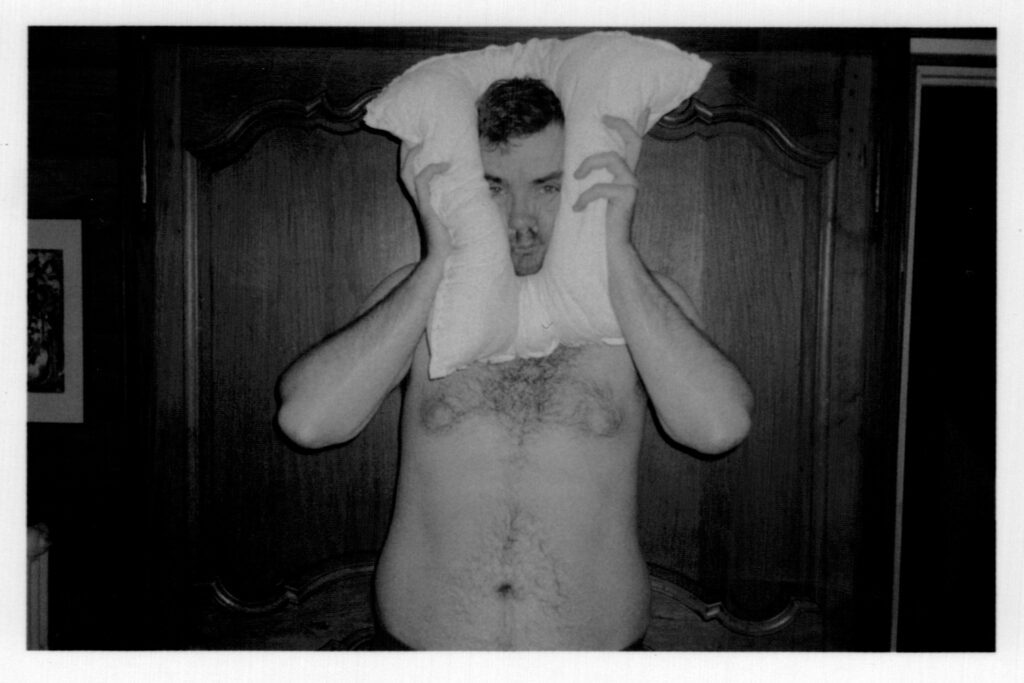

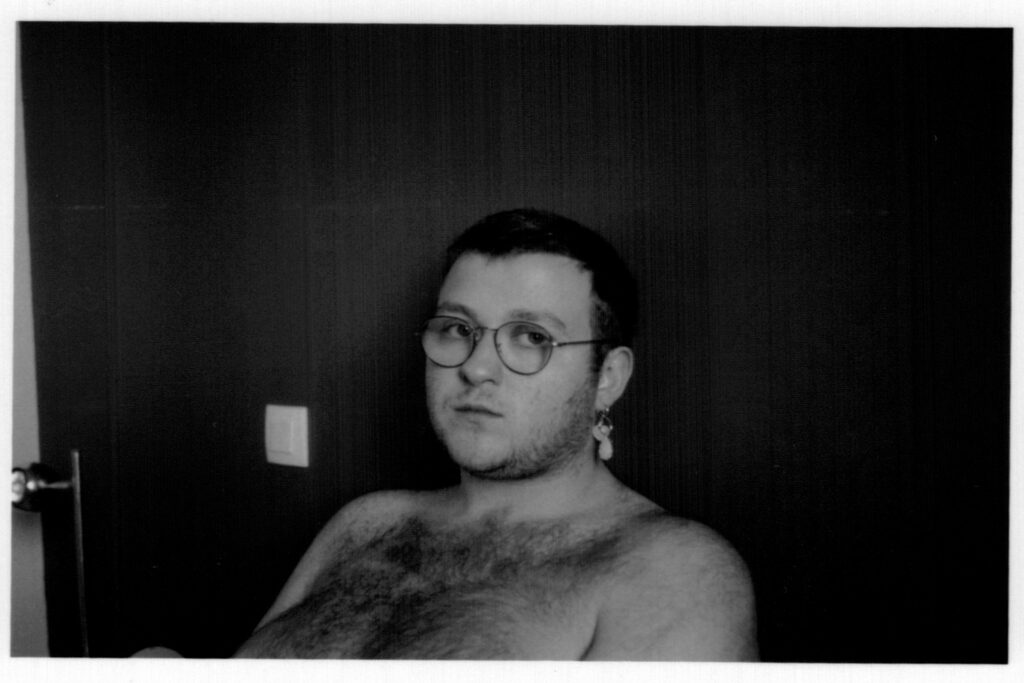

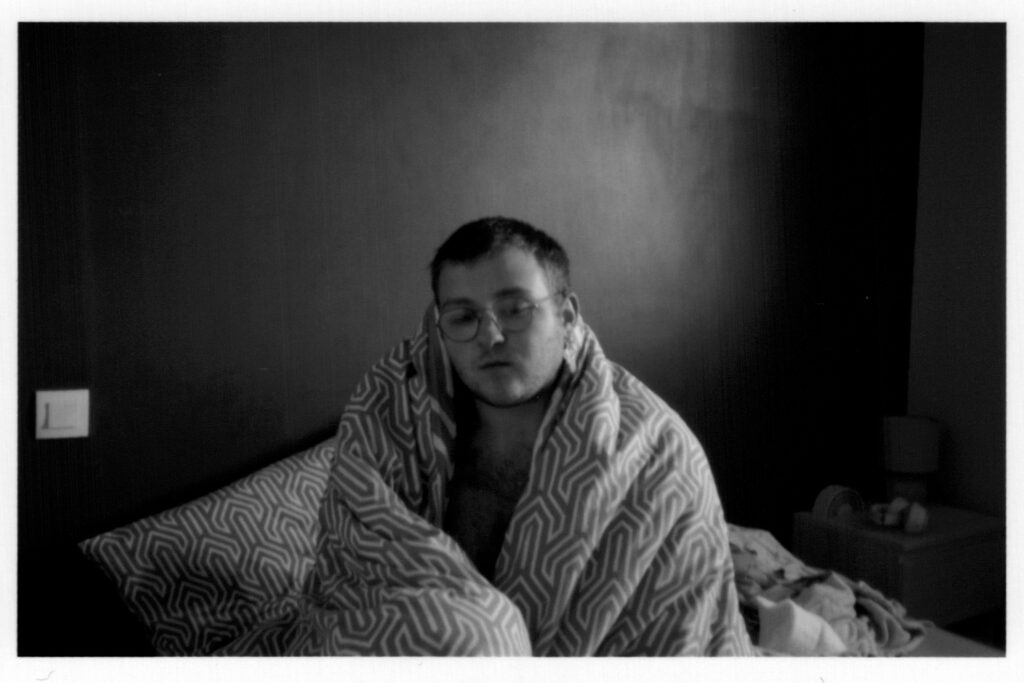

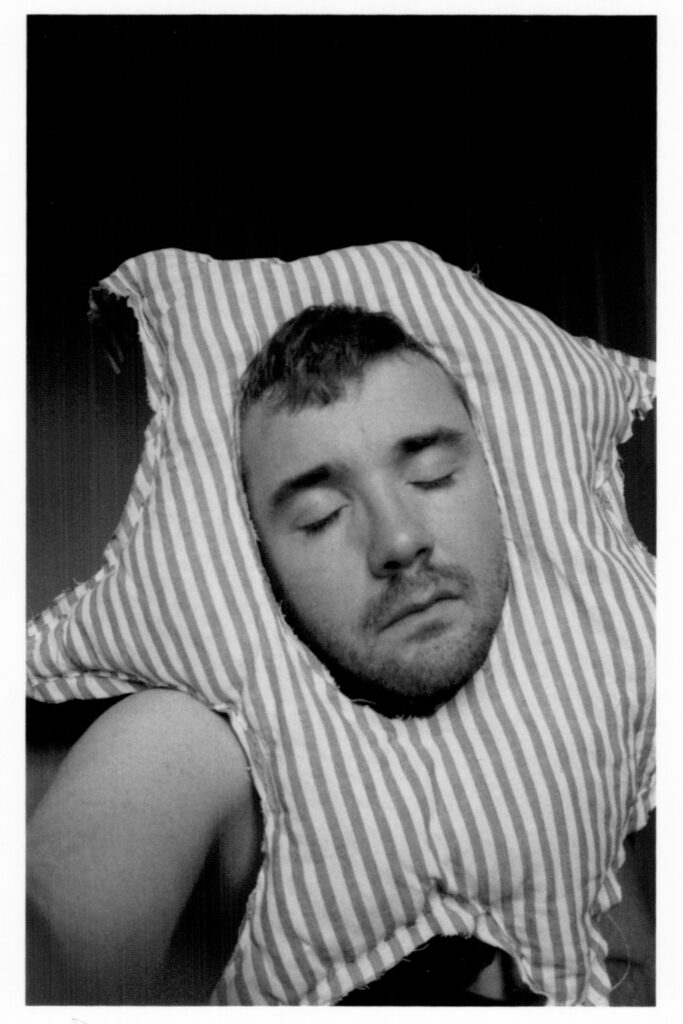

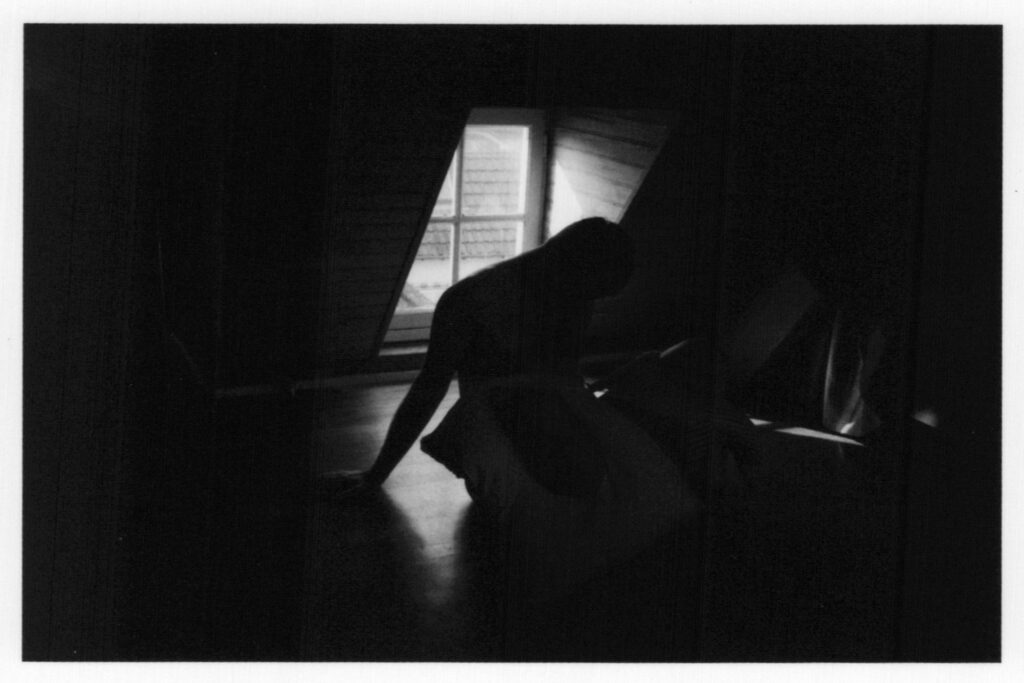

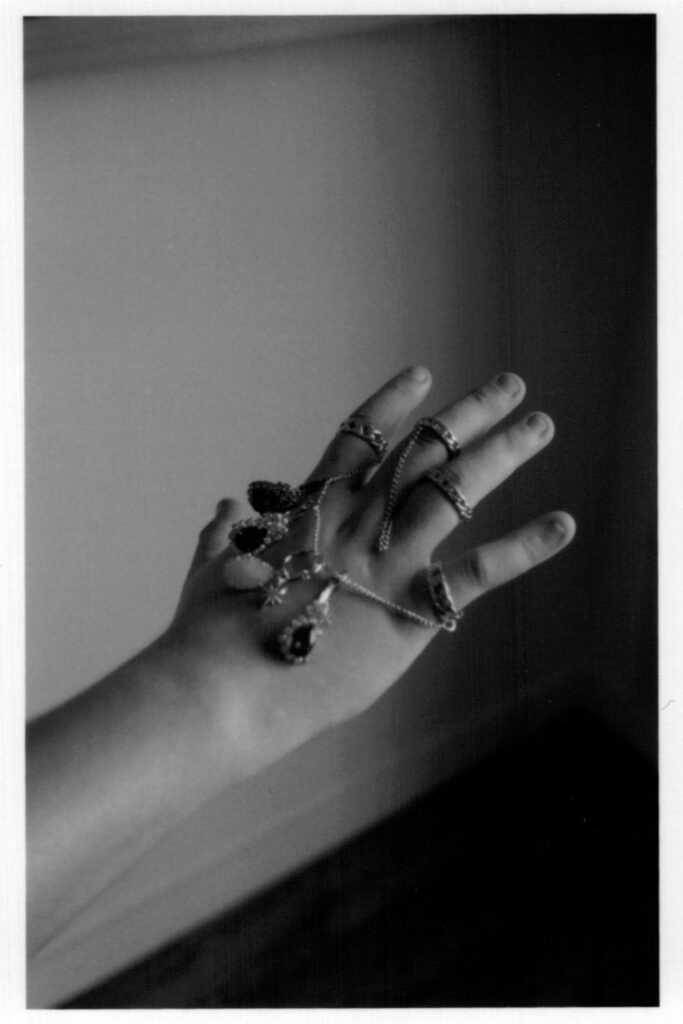

These relations often end the way they begin, in silence, almost like a tacit form of pure sexual consummation between two individuals. Occasionally they extend well beyond the traditional pick-up venues, making their way into the privacy of the home. By drawing on his own autobiographical experiences, Lepetit invites us to contemplate a nascent intimacy that is rooted in the home of another man. He shows us both a series of self-portraits and photographs of that other man, each in his own personal space. The artist simultaneously explores discovering oneself and encountering the other. He juxtaposes a family house that is filled with childhood memories and a “model” apartment, a “show” flat, filled with the same standardized furnishings that you can find elsewhere. Yet what is striking above all is the emotional intensity the photographs give off. The jewelry decorating a hand or ear, the hair on a torso, or the curves formed by a belly conjure up the vulnerability of poses that are almost stripped of all affect. While maintaining its resistance to heterosexual social norms, this encounter becomes an unexplored territory for human connections. Beyond the purely carnal aspect of gay pick-up places, cruising is revealed as an attitude that is steeped in openness and social and emotional availability to the other.

1. Christophe Honoré, Plaire, aimer et courir vite, Paris : Les Films Pelléas, 2018, 1:42:33-1:44:57 :

2. Walter Benjamin, “Paris the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Cambridge, Mass., London, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999.

3. “It is rather a game of hide-and-seek with this idea of public space. Pick-up places are never found in the public arena, that is, in plain sight, even when they are located in venues that are very busy. On the contrary, they offer a significant number of strategies for hiding, overlapping, or replacing public space inasmuch as… this exercise is a constituent element of the territory of pick-up places,” Adrien Le Bot, “Lieux de drague,” Trou Noir : voyage dans la dissidence sexuelle, no. 9 (26 November 2020).

4. Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, vol. IV, Sodome and Gomorrhe, tran. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin, with Andreas Mayor; revised by D.J. Enright, New York: The Modern Library, 1992.

5. Guy Debord, “Théorie de la derive,” Les Lèvres Nues, vol. 8/9 (November 1956). Vincent Pécoil, “Vito Acconci,” Critique d’art [online], no. 24 (autumn 2004), published online 22 February 2012, consulted 29 October 2023. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/critiquedart/1663.

Pierre Ruault, Stockholm, October 2023